Society–Knowledge–Discourse

A conspiracy is generally understood to be a secret collaboration between various actors to the detriment of third parties. There are numerous examples of conspiracies in history, some of which had considerable political repercussions, such as the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar in 44 BC.

A conspiracy theory is a belief system or explanatory model that interprets current or historical events, collective experiences or the development of a society as a whole as the result of a conspiracy. It is disputed since when conspiracy theories have existed in this sense, but there is much to suggest that they should be regarded as a historical constant , analogous to conspiracies.

Conspiracy theories became established as a subject of scientific research from the middle of the 20th century, particularly through texts by the Austrian-British philosopher Karl Raimund Popper and the US historian Richard Hofstadter. Popper described “the conspiracy theory of society” as the “secularization of a religious superstition” and associated it with totalitarian ideologies.

Hofstadter saw certain parallels between the tendency towards conspiracy theories and clinical paranoia and coined the term “paranoid style” in this context. Although this was explicitly meant not as a psychological but as a political category, Hofstadter’s associative linking of conspiracy theories and paranoia paved the way for a psychologization or even pathologization of conspiracy theory speculation.

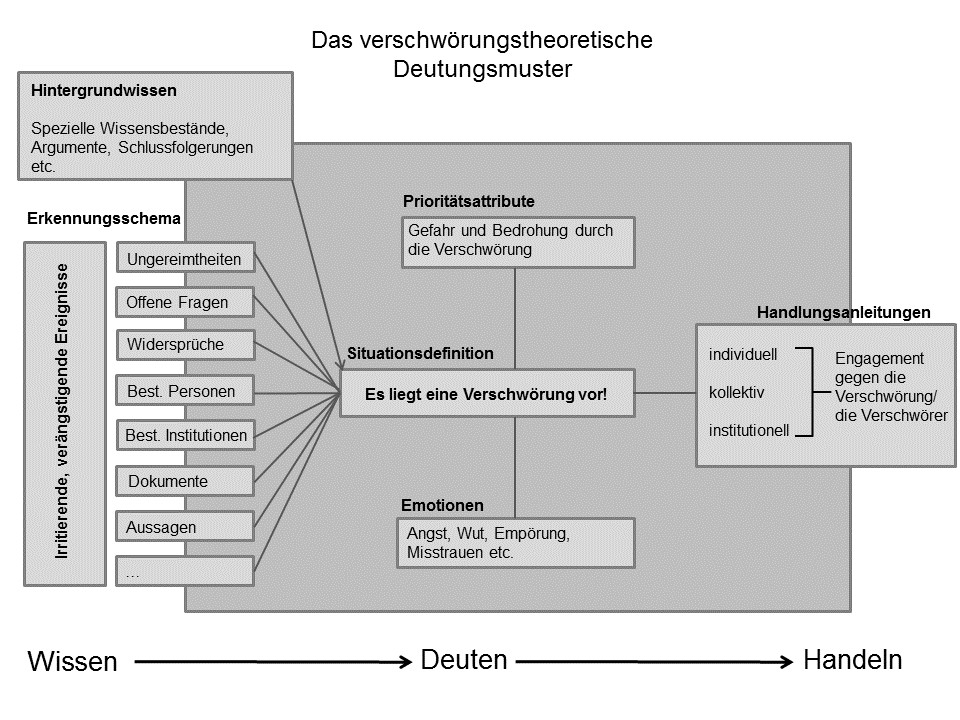

Fig. 1

The structure of conspiracy theory patterns of interpretation (Anton and Schetsche 2020).

Popper’s and Hofstadter’s ideas continue to shape research into conspiracy theories to this day. Particularly in the context of psychological and socio-psychological research on conspiracy theories, corresponding assumptions appear explicitly or implicitly time and again. Conspiracy theories are often regarded as irrational and illegitimate belief systems because they claim to have knowledge of conspiracies that, according to the prevailing (cultural and scientific) interpretation, do not exist or have never existed ‘in reality’.

The research perspective adopted at IGPP views conspiracy theories as a psychological and social phenomenon and, with the help of approaches from the sociology of knowledge and discourse theory, endeavors to develop a theoretically plausible and empirically viable sociological theory on the emergence and dissemination of conspiracy theories as well as their functions and effects as patterns of cultural interpretation.

Selected Projects

Der Kampf um die Wahrheit. Verschwörungstheorien zwischen Fake, Fiktion und Fakten

Conspiracy theories are generally seen as an expression of extreme political or religious attitudes, as part of dangerous ideologies or at least as illegitimate, false opinions or beliefs. This view of conspiracy theories dominated media and academic discourse even before the coronavirus pandemic and has since become even more important. From a sociology of knowledge perspective, however, framing the highly complex social phenomenon of ‘conspiracy theories’ in this way is problematic. It ignores a significant part of the spectrum of conspiracy theory interpretations and ultimately leads to a de-differentiation of the object of research.

In recent years, Andreas Anton and Michael Schetsche have presented a model of conspiracy theory thinking based on sociology of knowledge, which examines conspiracy theories through discourse analysis and systematically focuses on those processes of social knowledge and reality construction through which conspiracy theories in Western societies today are (generally) assigned to the realm of heterodox (i.e. generally unrecognized) knowledge.

Book cover: Anton & Schink (2021). Der Kampf um die Wahrheit. Verschwörungstheorien zwischen Fake, Fiktion und Fakten. Komplett-Media

The aim of the book project “Der Kampf um die Wahrheit” was to make the main implications of this model accessible to a wider audience as part of a popular science book publication. In addition, the current state of academic debate on the topic of ‘conspiracy theories’ and the history of the impact of various conspiracy theories were to be reconstructed. The sociologist Dr. Alan Schink, who completed his doctorate at the University of Salzburg on the subject of ‘conspiracy theories’ and has been in contact with IGPP for some time as part of various other collaborations, was recruited as a cooperation partner. Work on the book was completed in summer 2021 and it was finally published by Komplett-Media-Verlag in August 2021.

Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens (2., erweiterte Auflage)

Since the coronavirus pandemic at the latest, conspiracy theories have increasingly been perceived as a socio-political problem and have become a political issue. Never before has there been such a high level of sensitivity to the topic in public discourse. Fears of conspiracies on the one hand and fears of conspiracy theories on the other are apparently fueling each other. This is leading to growing social polarization and a climate of mistrust, outrage and irritation. Against the backdrop of the current public debate on conspiracy theories, in 2023 Springer-Verlag offered to publish an expanded new edition of the 2014 anthology Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens (edited by Andreas Anton, Michael Schetsche and Michael Walter). With six new contributions, the expanded new edition focuses on current developments. In combination with the original essays, the aim is to contribute to a comprehensive and differentiated picture of the social phenomenon of conspiracy theories.

Book cover: Anton, Schetsche und Walter (Hrsg.) (2024). Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens (2., erweiterte Auflage). Springer VS.

Further Publications

Anton, A., Schetsche, M., & Walter, M. (2024). Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens (2., erweiterte Auflage). Springer VS.

Väisänen, M., & Anton, A. (2024). Disqualifiziertes Wissen: Verschwörungstheorien im gesellschaftlichen Diskurs. In A. Anton, M. Schetsche, & M. Walter (Hrsg.), Konspiration. Soziologioe des Verschwörungsdenkens. 2., erweiterte Auflage (S. 35–53). Springer.

Anton, A., & Schink, A. (2022). Die konspirative Herausforderung. Zum individuellen und gesellschaftlichen Umgang mit Verschwörungstheorien. Bewusstseinswissenschaften. Transpersonale Psychologie und Psychotherapie , 28(2), 47–61.

Anton, A., & Schink, A. (2021). Der Kampf um die Wahrheit. Verschwörungstheorien zwischen Fake, Fiktion und Fakten . Komplett-Media.

Anton, A. (2020). Die verschwörungstheoretische (De-)Konstruktion der Wirklichkeit. Zur Wissenssoziologie von Verschwörungstheorien. In B. Frizzoni (Hrsg.), Verschwörungserzählungen (S. 61–74). Königshausen & Neumann.

Anton, A., & Schetsche, M. (2020). Vielfältige Wirklichkeiten. Wissenssoziologische Überlegungen zu Verschwörungstheorien. In S. Stumpf & D. Römer (Hrsg.), Verschwörungstheorien im Diskurs: Interdisziplinäre Zugänge. 4. Beiheft der Zeitschrift für Diskursforschung (S. 88–115). Beltz Juventa.

Anton, A. (2020). Willkommen in der Paranoia-Gesellschaft! Verschwörungstheorien in Zeiten von Corona . Zeitschrift für Fantastikforschung, 8(1), 12–19.

Anton, A., & Schetsche, M. (2015). Konspirative Wirklichkeit. Zur Wissenssoziologie von Verschwörungstheorien. INDES. Zeitschrift für Politik und Gesellschaft , 4, 33–42.

Anton, A., Schetsche, M., & Walter, M. K. (Hrsg.). (2014). Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens . Springer VS.

Anton, A. (2011). Unwirkliche Wirklichkeiten. Zur Wissenssoziologie von Verschwörungstheorien. Reihe: PeriLog. Freiburger Beiträge zur Kultur- und Sozialforschung . Logos.